Stop meeting people where they’re at. Take them to a better place.

It’s a mantra some communications people dole out like free samples at the supermarket: “Meet people where they’re at!”

On the surface, this sounds sensible enough. Why wouldn’t you start from a place your audience already understands? The problem is, this common piece of messaging advice is not only misleading, but outright dangerous.

Let’s be clear: it’s not wrong to seek connection. We should listen deeply and find ways of relating to our audience. But connecting with our audiences is not the same as validating or pandering to unhelpful narratives.

When we shape our messages to fit frames rooted in individualism, competition, white privilege, patriarchy or consumerism — just because they’re familiar — we risk reinforcing those frames and making it harder to build support for the world we really want.

That’s because when we think of something specific, the neural networks representing that concept in our brains start firing. And when neurons fire together, they wire together a little more. In other words, when we activate unhelpful narratives in people’s brains, we strengthen those narratives further still. If people currently hold unhelpful ideas about our issue, the last thing we want to do is meet them there.

In research into Australian discourse, we see this happening across many different issues:

When we frame gender equality as something that 'benefits everyone' to appease misogynists - rather than asserting that women and gender diverse people deserve to be valued and treated with respect – we reinforce the unhelpful idea that women can only have their rights upheld if men benefit too.

When we talk about the “economic contributions” of people seeking asylum, instead of our responsibility to support people seeking safety, we reduce people to their utility rather than affirming their humanity.

In health, when we emphasise “healthy choices” without acknowledging social determinants like housing, income and racism, we blame individuals for outcomes shaped by systems and so divert attention away from the real solutions that tackle root causes.

Frames matter. Values matter. The more we repeat a frame, the stronger it becomes—regardless of our intentions. When we “meet people where they’re at” in unhelpful frames, we’re reinforcing the toxic neoliberal, colonial, patriarchal worldviews that got us into this mess in the first place.

So what’s the alternative?

We know from cognitive linguistics and our own message testing on a range of social justice, health and environmental issues here in Australia that most people aren’t locked into a single worldview. Instead, we hold competing sets of values and frames that can be activated in different contexts. In other words, most people are flexible in their thinking and hold multiple (sometimes contradictory) beliefs about the same topic.

Someone might care deeply about fairness and community in one moment, and then react from a place of fear or individualism in another. Which part of them shows up depends, in large part, on how issues are framed.

That’s powerful. It means there’s no one place people are “at”. We don’t need to “meet people where they’re at” in unhelpful frames. We can meet them in the part of themselves that’s aligned with care, equality, responsibility, and solidarity. We can choose to speak to their more helpful values and frames—the foundations for building a more just and sustainable society.

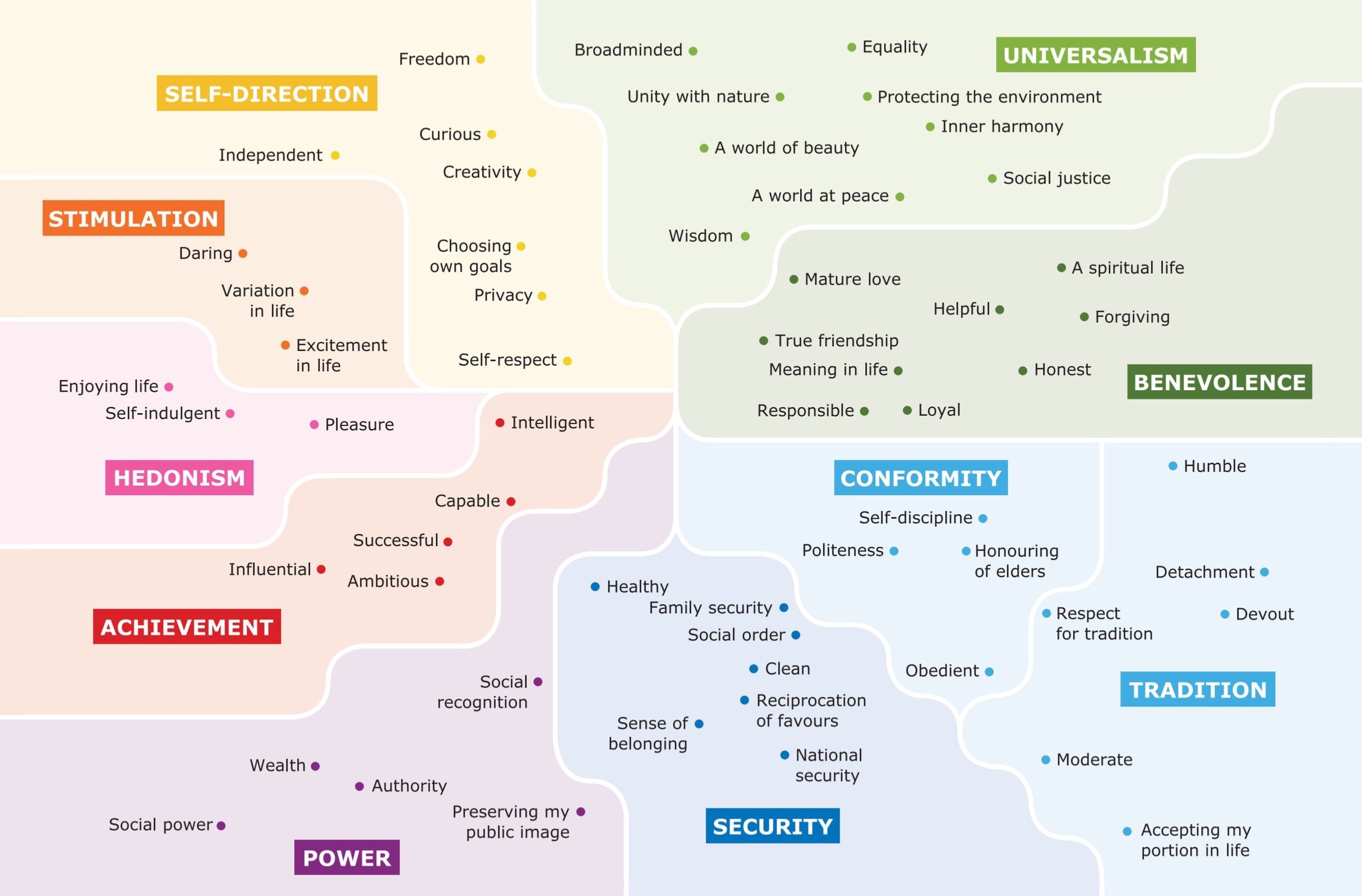

Our message testing with over 40,000 Australians across dozens of topics shows the vast majority of people can already see social justice, health and environmental issues from helpful perspectives steeped in values around self-direction, equality and care for others. Those are the green and yellow values in the values map below, which researchers have found are associated with more pro-social and environmental attitudes and behaviours in people around the world.

Importantly, when we consistently reinforce those helpful values and frames through our communications, we help strengthen them in public thinking. We make them more accessible, more familiar, and more likely to be activated in future conversations.

This leverages our familiarity bias, which is the cognitive tendency to prefer information, frames, or ideas that feel familiar. The more often a frame is repeated, the more normal and credible it feels. In the context of biconceptualism, this means that while people may hold both compassionate and self-interested frames, the more familiar one is more likely to be triggered.

This is why simply mirroring dominant public narratives in a mistaken attempt to gain traction can backfire. When we reinforce frames rooted in fear, individualism or competition, we make those frames more cognitively accessible. We don’t just meet people “where they’re at”—we make it harder for them to move.

The solution is to create familiarity with the frames we actually want to strengthen. That takes repetition, consistency, and courage—not just to reflect dominant public attitudes, but to shape them.

So stop meeting people where they’re at - if where they’re at is the problem. Instead, meet them in the best place they can go and have a much more productive conversation there.